Search This Blog

women in film & media

Production, distribution, reception

of films

Posts

Revisiting Katherine Hepburn in Venice: Summertime

- Get link

- Other Apps

Revisiting Ingrid Bergman in The Visit

- Get link

- Other Apps

Revisiting Bergman's The Seventh Seal

- Get link

- Other Apps

Queer Women of Color Film Festival, San Francisco June 12-14

- Get link

- Other Apps

The Eclectic 62nd Cannes Jury=Woman Power

- Get link

- Other Apps

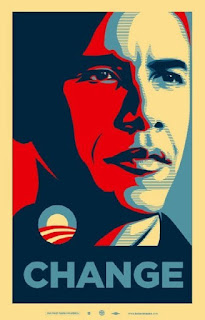

Gus Van Sant Gets Milk Nearly All Right

- Get link

- Other Apps

Journalist Ulrike Meinhof: From Theory to Practice

- Get link

- Other Apps