Search This Blog

women in film & media

Production, distribution, reception

of films

Posts

Jamie Babbit Closes Frameline; Andrea Sperling Receives Frameline 2007 Award

- Get link

- Other Apps

Born in Flames Revival at Frameline

- Get link

- Other Apps

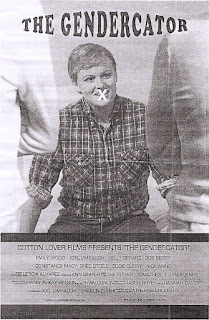

Frameline31 San Francisco Pulls Lesbian Film from Lineup

- Get link

- Other Apps

Third Queer Women of Color Film Festival, San Francisco, 2003

- Get link

- Other Apps

National Queer Arts Festival, San Francisco Kicks Off

- Get link

- Other Apps

Lesbian National Center for Lesbian Rights Celebrates 30 with Martina Navratilova

- Get link

- Other Apps

Ensemble Album with Swedish Lesbian Vocalist Eva Dahlgren Blacklisted by Bush

- Get link

- Other Apps